It’s all about the body

Contents

Chapter 2: 16:00-17:00

Addition for the m/other-us-all

Introduction

This piece of fiction picks up exactly where we left off last month. Originally, it was part of last month’s post, but I cut it out because the whole thing felt far too long. It continues the ‘Dip’ section of the chapter, though it feels quite different from what happened in ‘Bliss’ and the first part of ‘Dip’. It reads rather flat. It doesn’t develop Val or Graham as characters. It is, frankly, a bit dull – another reason I decided to cut it last month.

Since this is heuristic inquiry research, I found myself facing a dilemma. Do I make the fiction more appealing, rewriting it so it’s easier to read and, ideally, more engaging? Or do I stay true to my research process and trust that my tacit wisdom has produced something I need to hear as I continue the work of dismantling the particular master’s house I have found myself stuck in. If I refer to our growing mother-us-all (never a man-u-all), of course I will privilege process over product.

Last month’s fiction ended with Val beginning to sense the loss that comes from not being held in mind through/within the tacit maternal knowing I’m trying to theorise. She’s struggling with not having experienced that good-enough attunement from a powerful other who chooses to use their power in the service of a powerless infant. This tacit maternal knowing doesn’t place the infant in a ‘master’s’ role, demanding service, but rather sees the infant as an equal human soul to be cherished and enabled to flourish through the more powerful other’s choice to serve. That inkling sent Val into a reverie.

Part 3: Dip (cont.)

Val rarely thought of her mother these days. In the early stages of her relationship with Graham, he’d driven her to his home village. He took her to the village church and showed her the graves of his grandparents and parents. It felt like a formal introduction – and not in the least bit sad. She was surprised that she’d assumed visiting graves would be sad, just as she was surprised that, after the five-and-a-half-hour drive, this was the first place they stopped.

“Where are your parents buried?” he’d asked, as if that were a perfectly ordinary thing to say. Val had been a bit startled. It was neither ordinary nor normal for her to hold her parents in her realm of thought at all.

“My mother is still alive!” she’d said, her voice sounding much too loud in the quiet graveyard. She seemed to surprise herself as much as Graham.

“I’m so sorry.”

Graham shifted his weight from one foot to the other as they stood beside the green grass and carved stone that bore witness to his parents’ devotion to the land, family, and community. That commitment had worn them out – his father dying of a heart attack at sixty-seven, and his mother passing away just eighteen months later from what the family said was a broken heart, though the doctors called it undiagnosed cancer. It had caused no symptoms or pain, only a gradual loss of weight, until her very last two weeks.

“You’ve just never talked about them, so I assumed,” he said, looking down at his feet, feeling small and uncomfortable.

Val, still, barely breathing beside the legacy of his family that he so clearly wanted her to see and feel, had no words. Her feelings were like the dust her father became when he was cremated. Her mother had upended the urn on a windy beach along the coast where, Val imagined, they’d spent dull and wordless holidays after she’d left home. Her vision of her father’s disposal was all grey tones. She hadn’t been there. Her mother told her about it afterwards. She said she hadn’t wanted to disturb Val since she knew Val was working hard. Val hadn’t questioned it. She’d taken it as her mother being thoughtful.

“When did you last see your parents?”

For a moment, Val wasn’t sure where she was. Graveyard? Service station? Past? Present? It had been at the graveside, that conversation – in Alnwick, sun shining, wind blowing.

“Together? I don’t really know. I saw my mother at my father’s funeral,” she’d said.

Graham, absorbed in pulling an imaginary weed from the carefully tended grave, didn’t see the fleeting lines appear on Val’s forehead. She was bemused by her own disconnect from any human feeling. It wasn’t that she lacked compassion – she simply had no feeling about the man who’d been there in the house when she was growing up. Her parents were like figures in a comic or a play – somehow not quite real, yet still very real. But she could never have said something like, the world doesn’t feel real, not without risking having her ears washed out again.

Val felt a pressure on her hand. The overwhelming ghosts from her past took steps back at the warmth of Graham’s hand. She landed back in the service station, raised her eyebrows, and scrunched up her mouth, conveying dismissiveness.

It was a lingering pain in her life that, despite being a therapist, despite striving to be someone who cared, someone who made a real and positive impact on others, she was incapable of connecting with the people who should have been the centre of her own felt sense of safety. She felt again her internal reality: that she simply wasn’t good enough and had failed.

She coughed and looked at her watch. She had to press a button to light up the face in order to see the time, so she pulled her hand from under Graham’s.

17:00. Three hours. They’d been there three hours already.

It’s all about the body

This month has been a useful reminder of the post from March where I suggest, in a somewhat obscure way, that boredom is a necessary part of working out how our m/other tongue functions alongside the helpful aspects of maleness and fathering. Sticking with the structure of my research process, despite the dullness of the fiction, gave me another step forward in trying to create this elusive, practice-transforming theory, called tacit maternal knowing, to support us as we use our m/other tongue in our work.

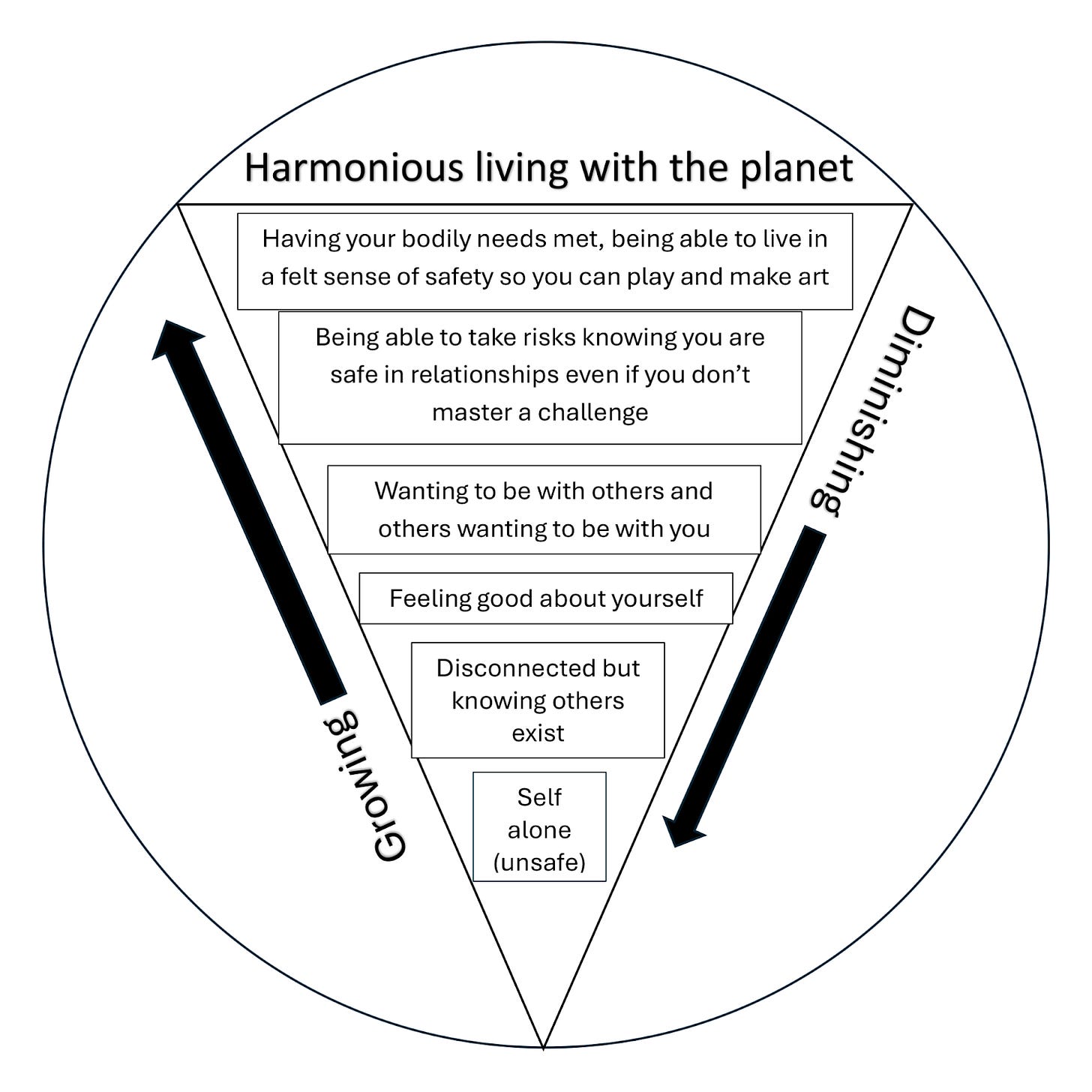

Way back in August 2023, before formalising these blog posts into a post-doctoral research project, I grappled with trying to make Maslow’s hierarchy of needs fit with my progression towards living with our m/other tongue. I was puzzled over how to get myself out of the toolbox of the manstream - I had yet to find the changing bag of the m/other tongue. At that point, I was trying to get the square peg of using tacit maternal knowing to shape my practice through the round hole of theory that had ‘worked’ for me; at that time it was Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943).

As I reflect on this again through another cycle of Heuristic Inquiry, I now see that Maslow ‘works’ if you’re trying to understand human motivation through the lived experiences of the WEIRD (western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) and the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (WSCP) because the theory is derived from those experiences. Maslow took the worldview of the Blackfoot tribe and reshaped it to fit his own perspective (Michel, 2014). If we share his worldview - if we live, or lived, similar lives to his - then his theory ‘works’. We - or I - therefore accepted his theory as ‘right’.

Now, I’m saying that this way of understanding the world no longer helps those of us who feel that such a worldview isn’t ours and indeed is contributing to the destruction of our planet. I see people conforming to that drive for self-actualisation through individualisation, where power equals money and the highest form of knowledge equals cognition, as intimately connected to the ecological, political, economic and societal disasters I see on the news on a daily basis.

The pervasive sadness I felt while reading the fiction last month has continued this month. It’s a familiar place to me: that never-ending sense of getting things wrong, even when I know I’m right in acting from a place of intended kindness and care. I feel I am right because I know I am striving to be a person who lives congruent to my beliefs, summed up in the person centred counsellors’ creed. Yet, because my striving, my heartfelt efforts, seem invisible to others because they are intimate and private, I feel dismissed.

As a child, when Val tried to express her distress to her father by saying ‘the world doesn’t seem real’, she was met with having her ears washed out. She felt obliged to say it was all better now, even though it wasn’t. Distress couldn’t be addressed in any meaningful way, just as Val, standing by the graveside, couldn’t think meaningfully about her parents. Engaged, relational connection – as well as the pain of its absence – was shut down by the apparent resolution of patriarchal thinking. And yet she stands there, in a field/graveyard, contemplating bodies/graves and how they add meaning to relationship. Nothing should be dismissed, nothing discounted.

So now Maslow doesn’t feel real. I don’t want to dismiss him – only to use the theory in the right place, at the right time, for the right purpose. I am working with tacit knowing and knowledge as the source of theorising. Polanyi (1973) says tacit knowledge is not languagable, so it can only be conveyed through skilful doing – through the tacit knowing shown in the act itself. Tacit knowledge, then, resides in the body.

So, in theorising tacit maternal knowing, I am seeing the body as the field of enquiry and the source of knowledge – not just the thinking mind.

How might this move our theory-building forward as we try to use our m/other tongue?

In my usual information superencountering, I was drawn to Frost and Holt (2024), Hadd (1991), and Inkle (2016). These were the first papers I uncovered as I tried to make sense of how previous scholarship challenges the objectification of women’s bodies. Reading them brought me back to Verrier’s (2009) writing on the primal wound, and to Winnicott (1990). I reread his writing about how we find our sense of a true self, first through relational connection with our mothers (or those others who make mothering available to us as infants), and then through the despair that comes when that primary maternal relationship is, for whatever reason, insufficient.

In infancy, we are a bundle of body. The fiction prompted me to reflect on how farmers sustain our bodies. Their bodily labour enables the land to feed us. Since Covid, bodies in space have been less present as we connect via video meetings. We are embodied beings, so I believe that not being in spatial connection leads to stress.

Think about Harlow’s monkeys (Suomi et al., 1971), separated as infants, able to hear and smell others, but unable to touch them. The separation was distressing. Reading the research and watching the videos on YouTube is also distressing. I struggle even with the ethics of referring to his research here. Was separation via ‘scientific detachment’ needed in those who conducted these experiments? Was this scientific detachment their cognitive shield against the distress they were not just witnessing, but instigating?

I often feel a kind of distress on a video call - able to see and hear but not smell or touch – but of course, I use my thinking brain to hide and suppress it, pretending it’s unimportant. I slip into that very human habit of pushing emotion aside to perform the role I have been given, or chosen. Is it necessary? Sometimes?

Such questions make me think again about why I am so compelled to churn out another post each month, another painful dredge of my tacit knowing. Another attempt to find language that lets us share what it means to live our work in our m/other tongue, to squeeze a three-dimensional lived experience into the flatness of a page.

I’ve noticed I’ve started to use the word vocation more often in recent posts, though I’m not sure I’ve defined why, or what I mean by it. For me, vocation carries the sense of ‘this is more than me’. In my life, this ‘more than me’ driver is how to enable flourishing in others through meaningful, compassionate, and congruent connection between living beings - and to feel fulfilled myself through committing to that way of being.

Living by vocation marks a fundamental shift away from individualism and the pursuit of concrete knowledge and wealth, towards fulfilment through service. It’s a calling that compels action beyond logic – and yes, it carries a spiritual dimension for me, coming from a Christian tradition of expressing that aspect of being human. This sense of vocation drives me to keep exploring these issues for myself, and try and share them with you.

The stress of disembodied existence is, I fear, becoming ‘normal’. I feel I’m pushing against the current – awkward, non-conforming, a grumpy old woman who won’t know her place. I chose not to make the fiction more appealing to please my followers, but to stick to my process in this Heuristic Inquiry. I’m not producing a product or seeking profit. I do want to share these ideas in the hope they might contribute to people living more fulfilled lives.

What I am talking about is slow, circuitous, non-productive, messy, and inconvenient. I’m saying we’ve got to get bodies in the room together.

The fiction is my anchor. You may have noticed from my writing that I can get drawn into big ideas and, dare I say, flights of fancy! Yet the fiction grounds me in the fact that we are bodies – and at the end of the day, when the body goes, the body goes. Do we go? Yes and no? What is ‘I’? Yep, flights of fancy and big ideas.

Death is both attractive and terrifying when you have never felt yourself to be anything, as is omnipotence, expressed by implying one has the answer to those big questions. This research endeavour began during my doctoral process as I tried to understand how I work with children experiencing the impact of relational and developmental trauma. The post The Life and Death of Hide and Seek attempts to illuminate for others what I know of the internal experience of the children I’ve worked with. I have tried to be alongside them as they come to know, as they engage with knowing the impact of the primal wound. I’ve tried to stay connected with them as they encounter (not think about) the loss of primary maternal preoccupation, and the terror of falling into nothingness.

Winnicott and Verrier both describe what I would call ontological insecurity, or existential terror. I see the link between their theories as the lived experience of feeling that simply being a body in the world is wrong. When no one can stay alongside the sufferer in that pain of wrongness, the pervasive sense of being wrong, the primal wound lingers. Without entering this place of terror, no coherent sense of ‘I’ can form, because ‘I’ arises through relationship, from the foundation of we. I am holding this alongside Winnicott’s idea that there is no such thing as a baby, and his concept of the me/not-me developmental phase (Davis and Wallbridge, 2014) - although Winnicott saw independence as the developmental end-point and I set out later in this post, I believe our m/other tongue needs to challenge that pursuit of independence as being the highest goal of development.

I come to this as a person in a body perceived as “woman”: born into a world shaped by misogyny, where what my woman-body does (menstruate, make babies, have breasts, go bonkers in the peri-menopause and so on) signals wrongness. My existence becomes a failure whichever way I turn, because I am not ‘normal’ as defined by the WEIRD and the WSCP. I am not ‘normal’ because I do not inhabit a male body (Criado-Perez 2019).

The children I have worked with are born unacknowledged as people, treated merely as objects to be managed or damaged. So they, too, are ‘wrong’. This goes beyond feeling; it is an embodied knowing. Heart, head, and hands – feeling, thinking, and doing – all knowing that fundamentally, you are just wrong. The primal wound lies in not being simply valued for being a body in the world.

What does that mean as we try to live using our m/other tongue?

Last month, I reflected on how we might extract ourselves from the toolbox of the manstream and create a changing bag for our work to help us use our m/other tongue. To do that, to find, fill, and use our changing bag, we must touch our own primal wound and that of those we serve because that is where the initial threads of connection lie. But naked vulnerability is in that place too.

Many of us, during our training, will have been in therapy and addressed our distress in that space, for our own self and development. However, here we are working out how we are professionals fulfilling our vocation, and I believe this calls us to a deeper exploration of bodily dislocation and naked emotional vulnerability of separation. We need to explore how such bodily dislocation and the lack of bodily connection informs our professional practices. That exploration takes place against a background where our tacit knowledge, acquired through innumerable muscular actions and stored in the body rather than in cognition or language, is seen as ‘wrong’ by the majority within the WEIRD and WSCP. We really are not going to be able to dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools and toolbox.

It’s becoming harder to just allow the fiction to unfold while I develop this theory through monthly posts, outlining this open-air Heuristic Inquiry process. I want to jump ahead, to digest the whole thing. I want to be at the end of the endeavour – to gather all these ramblings into a coherent publication that can offer a more conventional account of how we live and work using our m/other tongue.

But taking motherhood as our reference point, we know that to rush the growing up process causes distress and potentially trauma. To hastily foreclose on meaning in favour of speeding towards resolution can create further problems, born from insufficiently worked-through complexities of climbing out of the sticky toolbox. Without slowness, circularity, mess, and that boring waiting around, we risk ending up with nothing more than fast-food fixes that leave us with indigestion.

These fast-food fixes arise not from genuine hunger, but from distress at being unable to progress, from avoiding the block in the road ahead (seen through the lens of the tacit knowing expressed in the fiction). Such gaps in progress need holding. They are about taking the non-problem seriously. Holding happens through sticking with the process, setting aside the outcome, resisting - sometimes stubbornly - the pressures of the WEIRD and the WSCP, and being pedantic, grumpy, slightly awkward, and yes, very, very boring. There are no major transformative peak experiences here in the m/otherland. No fast fixes. Just connection and unfolding.

Leadership - operationalising our m/other tongue - is about enabling growth and change. Perhaps maturation is the better word. The word growth might drop us back into the toolbox if it’s heard as a manstream word, where productivity, rather than the depth and breadth of relationship, is the measure of that growth. Object-growth rather than relationship-growth, I might term it.

The fiction is about the nature of relationship: how Val and Graham are maturing within, and then away from, the relational field they were born into. It’s not about the product - which, in the case of the fiction, would simply be them reaching the destination of their journey.

Let’s drop the fancy language. This is about how we love others in ways that do not exploit them, and that serve their needs, not our own. Yet human needs are entwined; we are interdependent. Our humanity is affirmed through our care for others and for the world around us. At least, mine is, even if the story/world I was raised in (1970/80s England) hauls me back to the sticky toolbox, leaving me feeling that to care is wrong, weak, foolish – in a word, womanly or maternal.

Birthing is all about bodies; the body of the mother, the body of the baby, and the separation of bodies at the time when there is sufficient maturation that bodily separation is survivable. Once separate, connection has to happen across the gap between bodies. That begins through body-on-body communication;feeding and touch, as well as olfactory, auditory, and to a lesser extent, visual means.

Maslow, in developing his theory of motivation, of human readiness to change, flipped the Blackfoot understanding of the purpose of being (Michel 2014). If we continue to use the WEIRD and the WSCP as the foundation for theory, if we keep dipping into the toolbox and assume that the aim of life is self-actualisation – and that then becomes what motivates us. What if we, respectfully and in a way that is culturally appropriate for living by our m/other tongue, hold an alternative theory in our changing bag? So I flipped Maslow.

If we take this ‘flipped Maslow’, then the growthful or maturational direction of change is towards merging with the earth - the corporeality of being with people in a place at a time with the intention of finding the overlaps and connections to span any bodily dislocation. ‘Being the best’, in this ‘flipped Maslow’ is the nadir of diminishment as it involves separation from others through judgements of value being applied. This is not to devalue individual skill or insight, but in our m/otherland we’d see those in the context of value to the community as a whole and a sign of our connection and safety in being together.

In the WEIRD and the WSCP, ‘being the best’ can lead to separation and isolation because of the need to protect and monetise one’s property (remember the experience of me trying to register m/other tongue as a trademark!)

When that need ‘to be the best’ - or, as I would see it, the need to create an illusion of a purposeful life because one is isolated - is unmet, distress follows, and distorted ways of managing emerge. If, in their isolation, someone is seen and met in a good-enough way – if the baby is related to, the worker, client, or service is recognised where they are in their lost individuality – the next stage of progression is the emergence of something like a theory of mind, an ego state, or what Winnicott calls the sense of me/not me. A gap appears that must be bridged, because two beings are now aware of each other and desire connection. This drive to bridge the gap leads to shared experience – what we might call attachment. Attachment lays the foundation for play and creativity, as there’s now a sense of a potential audience, even if the way to spanning the gap is not yet known. Hope is born.

I found reading about the ways in which actors create bodily presence on stage helpful as I developed this next idea (Noe 2012, Narayanan 2021). With a sense of audience and the desire to reach across the gap, motivation grows to feel good about the self that reaches out. This allows one to feel both good about oneself and confident that the other feels positively towards you. From here develops a sense of belonging – of wanting to be with others and knowing they want to be with you.

Such belonging makes it possible to make mistakes and take risks, to play and create art. The individual’s drive to make and create is received into an audience space – the attentive mother, the enabling therapist, the receptive researcher, and all those other unnamed, often invisible caring professionals such as librarians. Finally, we become a body of people, merged with creation, interdependent in a safe and fulfilling way because we are also community, the corporeality of being at one with others and the world is our bliss experience - a high plateau, not a peak.

When there is enough creativity and play, that human need is satiated. Then, there can be a desire to carry that shared, embodied, unworded experience of togetherness into thought and language, so it may be externalised and transmitted – in inevitably truncated form – to others who did not participate in the experience itself. We begin on the downward side of the flipped-Maslow.

There is no stopping in this movement, no final destination. Instead, it is a continuous process: the beauty of embodied connection, the challenge of conveying non-verbal delight through verbal means, the inevitable sense of loss that accompanies translating tacit knowing into language, and then the return to a renewed state of harmony. This flipped-Maslow sits within a circle, representing the world turning without pause. To stop would be disastrous.

So why has the mansteam become so fixated on ‘fixing’ and reaching a peak? The changing bag is always ready for the next time the baby needs to be cared for: it is not a one-off experience.

Here lies ontological safety: no need to fight for space, only the capacity to enjoy overlaps between people and to be curious about differences, knowing they pose no threat and that things will keep moving with us, around us, in us, and for us - and that us means all of us.

It feels a little sad that, written down, some of the loveliness of the experience of making sense of my story, exposed to me by fiction, is lost – that trying to find language fixes us mid-process. Yet in this generation of theory, as we explore our m/other tongue within the WEIRD and WSCP, cognition is our point of meeting. In the therapy room, the manager’s office, in our data gathering, and as we educate others, we can aspire to reach corporeal merger by considering where people are on this maternal process of maturation and helping them towards the next stage. I now need to work out how being a Theraplayer helps us do that… thankfully, we have many more months to come!

And as ever, this is Heuristic Inquiry, driven by an individual desire to make sense in the belief that within the personal lies something that may be of broader, possibly universal, importance (Moustakas, 1990).

What do you think? Might there be real merit in a flipped-Maslow – a theory of human motivation and change generated through our m/other tongue?

Addition for the m/other-us-all

It’s about the bodies. It’s about being slow and messy and things having to be repeated. How do we make space in ourselves to let that be? How do we love, and let ourselves be loved?

Bibliography

Criado-Perez, C. (2019). Invisible women: Data bias in a world designed for men. Abrams Press.

Davis, M., & Wallbridge, D. (2014). Boundary And Space: An Introduction To The Work of D.W. Winnincott. Taylor and Francis.

Frost, N., & Holt, A. (2014). Mother, researcher, feminist, woman: Reflections on “maternal status” as a researcher identity. Qualitative Research Journal, 14(2), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-06-2013-0038

Hadd, W. (1991). A Womb With A View: Women as Mothers and the Discourse of the Body. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 36, 165–175.

Inckle, K. (2010). Telling tales? Using ethnographic fictions to speak embodied ‘truth’. Qualitative Research, 10(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348681

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Mearns, D., & Thorne, B. (1988). Person-centred counselling in action. Sage.

Michel, K. L. (2014). Maslow’s Hierachy connected to Blackfoot beliefs. https://lincolnmichel.wordpress.com/2014/04/19/maslows-hierarchy-connected-to-blackfoot-beliefs/

Moustakas, C. E. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage.

Narayanan, M. (2021). Space, Time and Ways of Seeing: The Performance Culture of Kutiyattam. Taylor & Francis.

Noë, A. (2012). Varieties of presence. Harvard University Press.

Polanyi, M. (1973). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy by Polanyi Published by University of Chicago Press. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Suomi, S. J., Harlow, H. F., & Kimball, S. D. (1971). Behavioral Effects of Prolonged Partial Social Isolation in the Rhesus Monkey. Psychological Reports, 29(3_suppl), 1171–1177. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1971.29.3f.1171

Verrier, N. N. (2009). The primal wound: Understanding the adopted child. BAAF.

Winnicott, D. W. (1990). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development. Karnac.