The craft of maintenance: m/other tongue, epistemic gestation, and the wonder of growing together

Contents

Listening, waiting, discovering — epistemic gestation

Having a laugh: no manual, just a m/other-us-all

Introduction

Hello, dear friends, and welcome to 2025!

I’m delighted to have you with me as I embark on another year of writing and discovery. This year, I want to explore this experience I named ‘tacit maternal knowing’ more widely. I want to share with you how I see Theraplay as something far more than a clinical tool. I want to show how using Heuristic Inquiry helps me, and I hope you, find ways to use expanded theoretical underpinnings to make differences in the lives of others. I want to keep picking away at the things that stop me, or divert me, from applying this knowledge, this tacit maternal knowing expressed through the method of Theraplay, for the benefit of those I care for in my professional practices.

I’m starting to call this ‘being a Theraplayer’.

This ‘unpicking’ is what makes this writing ‘research’ (in my opinion — feel free to debate). As I research, I position myself as a clinician, as a therapist educator, as someone who leads others, and as someone who researches. I am a practitioner researcher, which brings a particular flavour to the process. I hope this means that what I write could be applicable, whatever position you are in. This is research not for intellectual indulgence, but to support the cultivation enabling relationships that make the world a better place.

Those of you who have been with me on this journey so far know that ethical approval for my unpicking to be ‘research’ was given in July 2024, and November 2024 was spent generating new data in the form of a 56000 word novella written as part of NaNoWriMo. Now the next steps of the project begin.

To start with, I have given the project a working title:

Speaking in our m/other tongue: We do know – a Heuristic Exploration of how to operationalise tacit maternal knowing in psychotherapeutic practice, in the education of therapists, in the management of organisations with care at their heart, and in research practice

I’m glad you are there because this feels daunting, and I value both your company and that you will keep me accountable. I want this to be useful, and speaking directly to you like this helps to stop me going off (too far) into the land of ivory towers and intellectual pleasure.

So, dear friends, I wish you happy reading, challenging reading, exciting reading, thought-provoking reading, comprehensible reading, and useful reading. And I also ask you to tell me if at any time my writing fails to deliver on any of those!

And of course, I wish you a Happy New Year.

Fiction: Ear of a craftsman

It felt stressful walking into the jewellers — not something he usually did. Even the door had confused him: it didn’t open when he pushed it. It took some moments of perplexity before he realised there was a bell to press and that he was inspected through a camera before a security guard opened the door to allow him to enter. He’d phoned the shop before coming and been offered an appointment. He’d assumed it was just the jeweller being thoughtful, but now he realised that without that, entry would not have been permitted.

The guard, or host, or shop assistant — he wasn’t sure how to address her in his mind — indicated towards some seats with an open palm.

“Mr Waters will be with you shortly,” she said.

Graham dipped his head awkwardly in recognition and felt himself wheeze slightly as he sat, perched in tension on the edge of the seat. He felt the ring in his pocket, the wrong size for his fingers, but there and solid. The hard edges and the dimples of the beaten silver recalled his brother's pride, and his father's unimpressed look, when his brother had returned from a holiday in Italy proudly wearing jewellery. He knew his father hadn’t meant anything by the stern looks…but that wasn’t entirely true. His father's not knowing how to respond was expressed in that look, and Graham could relate to the potent mix of defiance and deflation in his brother — he could recognise it because he’d experienced it.

Graham slid further back in the seat and allowed himself to relax a little, accepting that his head and his feelings could say different things. He allowed his eyes to shut momentarily in this new and untested place.

“Sir, Mr Waters will see you now,” the guard intoned over his moment of reflection, her tone somehow hushed and reverent.

The jewellery workroom was wooden, that had been Graham's first impression: full of wooden benches, drawers, and stands for small metal implements. Mr Waters seemed like an extension of the room, rather than the master of it.

“What can I do for you?” He asked Graham, his voice much higher in register than Graham had expected.

As with the guard, he was steered to a seat not by voice, but by an open-handed gesture. Mr Waters' motion was such that not only did it invite sitting, but also exhalation. It seemed so much more than movement.

***

Graham looked at his watch as the door to the jewellers closed behind him. His eyes widened slightly and, without realising what he was doing, he pulled his sleeve down and up again as if the gesture might bring the time on the face of the watch back into alignment with his internal sense. But no, the watch face remained the same. He’d spent how long in there?!

He’d gone in to buy a ring for Val. He wanted to say how much he valued their relationship and yes, he did want to mark it in some tangible, visible way. He’d thought while he was there he’d see if the jeweller could make his brother's ring fit him. He ended up telling stories of his life, his brother, Val’s family, his broken ankle, and, as he spoke, the jeweller sketched.

“I will make this for you,” the jeweller said at the end. “In silver.”

The orb was made of two filigree trees of life, roots, trunk, branches. Joining the two was his brother’s ring, a band that encircled and created the orb.

“I’ll hinge one tree here,” the jeweller had said, indicating the roots with a sharp pencil tip. “And here, there will be a clip, and here,” he pointed to a third space. “I can put the bail here — for a chain if you want one.” He reached for a drawer above his workbench. “Inside, I will put these.” He tipped four small turquoise coloured pieces onto the bench.

“What are they?” Graham asked.

“Sea glass. The forgotten items of others, seen as rubbish, and turned over again and again by the sea until that action takes off the rough edges and harsh shininess, leaving us to find this magic.”

Graham thought that if Val had delivered that speech, she would have met his eyes and their smiles would have bounced between them, increasing with each moment of connection. The jeweller had just kept his eyes and his pencil on the sketch, his voice steady and factual.

Graham hadn’t hesitated. He winced at the price, but this man had heard, really heard. Graham felt ever so slightly drunk and disoriented as the door of the shop shut behind him.

Listening, waiting, discovering — epistemic gestation

I don’t really know where to start. And, at the same time, I know exactly where to start. I was surprised at the vehemence of my resistance to the word ‘innovation’ in my catch-up piece last month. It was that strong affective response that highlighted for me that something was going on there! Something I needed to explore more and that in some way does relate to this project I’ve undertaken.

As I reflected on my reaction to the word innovation, I found it seems to sit somewhere specific in me. It connects, it seems, at quite a visceral level to the manstream and all that evokes in me around the impact of the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (as bell hooks would have it).

It touched on something about the ingested messages that the only way to be acceptable is to be fast, coming up with new, novel ideas purely to support productivity in terms of contributing to profit for the ‘masters’. The use of the term ‘master’ is linked to that Audre Lorde position of a master, the one whose house we can’t dismantle using his own tools. It catches in me a deep anxiety that I am not good enough, that what I currently do is not good enough, and that I will only be acceptable if I ‘do better’ in terms of giving the ‘masters’ what they want. It is so far removed from the position I began to own through my doctoral research, a place where I could say ‘but what if what I do is magnificent already’ as a way of reclaiming tacit maternal knowledge as ‘real’ knowledge for practice and for academia.

However, the fiction situates the word master as a Master craftsman. This gives a whole new flavour to the word. Such a Master is someone who enables their apprentice to immerse themself in experiences that mean they can replicate the quality of work the Master can produce, or in the case of the fiction, enables Graham to find insight made concrete in a beautiful object.

Tacit knowing, as Polanyi (1973) puts it, is about working with the ‘more than we can say’ experiences of our expert application of practice. Our practice is that of using relationship for the wellbeing of others. The fact that I need to use words to try to share experiences with you is limiting. Just that one word ‘master’ has evoked different feelings and means different things in me. I don’t know how it has landed with you. How hard it becomes to be connected when our relationship is only through these words in this blog post!

That is where I hope the fiction can go beyond words. I hope it can evoke feeling, be affective, create spaces for thought and curiosity. I hope fiction means you can find your own meaning, do your own unpicking and sense making of experience. If you want to explore fiction as research, I recommend Leavy (2013).

I don’t know where to start in understanding and writing, but I do know where to start in the process of seeking understanding. I know how to be process orientated because that is a part of using our m/other tongue in our practice(s). I do know that tacit maternal knowing, the use of our m/other tongue, is about facilitating the growth of others through the choice to use our power in the service of the less powerful other. This means, I believe, we must be process orientated; we must listen, observe, wait and, as the Theraplay core conditions tell us, remain in the direct here and now experience while being responsive, attuned, empathetic, and reflective. It is a ‘being’ experience, not a ‘doing’ experience.

My endeavour, however, is seeking to take an experience of being and make it shareable through words — that’s what I mean by ‘operationalise’. The words ‘operationalisation’ and ‘m/other tongue’ can get in the way of sharing the experience, as well as, I hope, becoming a way for us to discuss the ‘more than we can say’ as a ‘linguistic shortcut’ to meaning through this messy process of exploration. I hope ‘operationalising our m/ohter tongue’ will become a way to share how our tacit maternal knowing is the knowledge that leads us, through our commitment to not knowing/letting go, by living with a reality of dependence/interdependence and through faithfulness, to be able to use our power in the service of the less powerful other by caring for people. That is a distillation of the many things I’ve blathered on about in the previous posts.

This is a research project. I have a methodology. The methodology guides me with a set of thought through why we do it this ways, as well as methods, the what we dos. My methodology is Heuristic Inquiry. That, therefore, gives me an anchor for the process of seeking meaning.

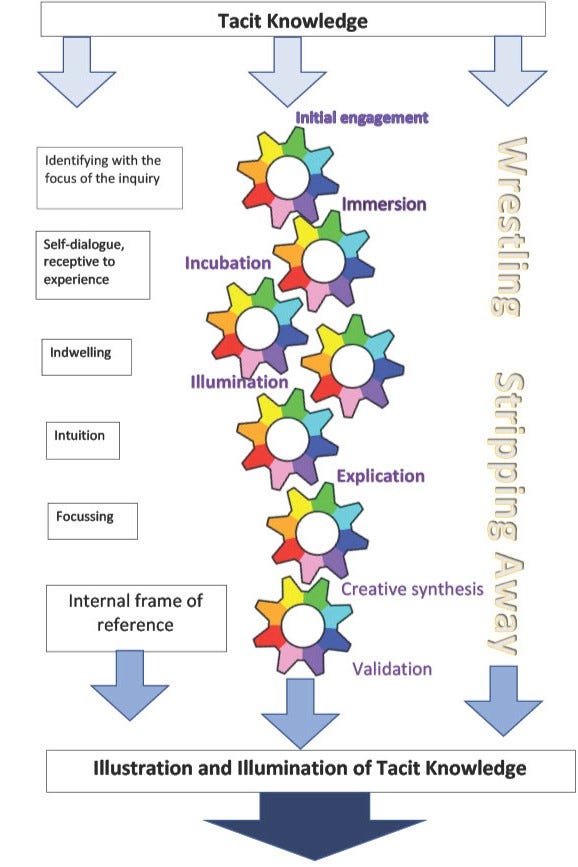

I developed the above graphic as part of my doctoral research (Peacock 2023) to represent the stages of Heuristic Inquiry that Moustakas (1990) identified. I added the wrestling and stripping away process to Moustakas’ original set of processes and points of focus. At the moment, I/we are in the initial engagement and immersion phases of this inquiry. I am identifying with the focus of the inquiry and in writing about it, hopefully I can inspire you to be curious too. I am hoping that, to paraphrase Moustakas, as I explore my passion of Theraplay as a way of being that could revolutionise the world, you will also find things that are truths for you too. I hope what I write may lead to things that have significance beyond just me and my practice. And yes, immersion at times can feel like I am drowning — and wrestling.

I come back to the fact that this is a research project. As well as a methodology, I have methods that are not just about data generation and data gathering. I am an information super-encounterer (see Seeking fulfilment through our m/other tongue) and in my post-birth stupor (56000 words, that was one big baby, I’m still recovering!), I am finding I am using my information super-encountering skills to try to wrap my head around what on earth I might have produced.

As I immerse myself, I have been reading all sorts of things and having all sorts of thoughts and following all kinds of threads. As I drown (and wrestle), they are like lifelines I hold onto. A bit like Graham, I feel in an alien place. I’ve come with ideas and I feel a bit disorientated when things take a different turn: out of my depth, floundering, but also feeling there is something important going on.

I’ve read about soil repair practices (Millner in Papadopoulos et al., 2023). About labour politics, arts and neoliberalism in Harvie (2013). Ottinger (2023) introduced me to the notion of responsible epistemic innovation, making me reflect that I do need to find words to convey enough about the labour of care that I am engaged with in my practices as a Theraplayer, because without those words such labour becomes invisible.

But I am still resisting the notion of this being innovation, hence my term epistemic gestation - I am hosting, giving internal space to, feeling growing within me, the development of a way of talking about a form of knowledge that my doctorate showed was sidelined through the workings of the patriarchy and the impact of misogyny. Gulari et als (2024) brought the maintenance art of Ukeles to my realm of knowledge and got me thinking about whether tacit maternal knowing is maintenance art in itself, or a maintenance craft. And I have been found by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, who has words for what I am trying to say far more clearly than I can say at the moment.

Care is too important to give it up to the reductions of hegemonic ethics. Thinking in the world involves acknowledging our own involvements in perpetuating dominant values rather than retreating to the sheltered position of an enlightened outsider who knows better. Can thinking be connected if it pretends to be outside of worlds we want to see transformed, even those we would rather not endorse? My intention in this book is not to stage a detached confrontation with mainstream notions of care, nor even to deconstruct or police sentiments about care as something that warms hearts and relations—such as the expectation that care brings good—but rather, to propose modes to contribute to its re-articulation, re-conception, and “re-enactment” (King 2012). This requires taking part in the ongoing, complex, and elusive task of reclaiming care not from its impurities but rather from tendencies to smooth out its asperities—whether by idealizing or denigrating it. Certainly to reclaim often means to reappropriate a toxic terrain, a field of domination, making it again capable of nurturing; the transformative seeds we wish to sow. It also evokes the work of recuperating previously neglected grounds. But more important for the approach to care in this book, reclaiming requires acknowledging poisons in the grounds that we inhabit rather than expecting to find an outside alternative, untouched by trouble, a final balance—or a definitive critique. Reclaiming is here all but about purging and “cleaning” a notion; rather, it involves considering purist ambitions—whether these are moral, political, or affective—as the utmost poisonous. Reclaiming as political work points to an ongoing effort within existing conditions without accepting them as given. It implies not shying away from what is important to us only because it has been “recuperated” by power, or by hype. This effort is for me an attempt to prolong a style of thought learned through feminist efforts to foster solidarities between divergent feminist positions without erasing unresolvable tensions. (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017, p.10)

Sacred maintenance

Having read Gulari et al. (2024), I am puzzling over whether mothering is maintenance, and if mothering is maintenance, how do things progress in our practice when we are led by tacit maternal knowing? And if it is maintenance, is it art or craft?

Then I catch myself. Graham in the fiction is going to buy a ring for Val. Is he thinking about some sort of marriage? What does their relationship mean when he is male and she is female, given the whole historical political legal positioning of ‘marriage’ in the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy? I think I am struggling to navigate that challenge Puig de la Bellacasa has given me — to not throw babies out with the bath water, if I were to bring the thinking back to the maternal care sphere. But to extract myself from falling back into manstream ways of thinking (represented by Graham even contemplating marriage), I have been needing to repudiate the interdependence of maleness and femaleness, otherwise I can find myself becoming re-entangled in old, limiting ways of thinking, feeling, and being.

That feels like a key thing in the operationalisation of our m/other tongue: am I choosing, or do I feel forced? Under the manstream, I have felt eternally judged as failing to see what I should be focussing on. Because I am scrabbling for time to focus on what the manstream says is important, what I believe to be important is pushed to the bottom of my to-do list. Then, in a neat double bind, my inner manstream feeds back — see, you weren’t any good at it anyway, you didn’t give it enough time, you haven't explained it well enough or made a strong enough argument. I feel overwhelmed and give up.

Millner and Ottinger helped me break out of my stuckness. Ottinger helped me see how important it is to find some kind of words for this epistemic place, this different (not necessarily innovative because people have been mothering for as long as there have been humans) way of placing what we do in our work into the arena of theory. Struggling for words to represent it doesn’t need to undermine or overshadow the actions of care. I am good at my job, I care about and care for people. It is just not easy to find the words to represent the ‘more than I can say’ — which is where the arts and skilled crafts come in.

To re-articulate, re-conceptualise, and re-enact care rooted in tacit maternal knowing—without demonising the patriarchal constructs that have marginalised such knowledge from academic and theoretical domains—I must find my voice. I need to articulate my embodied, felt sense of what it means to be a Theraplayer across all aspects of my life.

However, my faulty, stuck patterns of thinking often lead me to slip into the habitual belief that ‘progress’ is the sole measure of value, rather than one of many valuable dimensions. This mindset overwhelms me, leaving me feeling like a failure in the eyes of the manstream. Or indeed, my old-fashioned habitual thinking tells me ‘progress’ should involve a complete departure from previous actions, a revolution not an evolution. The progress I want to claim here is finding ways to show and share the knowledge that Theraplayers use professionally, albeit tacitly — not go change that knowledge or practice.

When considering tacit maternal knowing and using the lived experiences of mothers and infants as a foundation for theory, we inevitably move away from the idea that as human beings, we are ‘in charge’ of a process and can ‘make’ things progress. Mothers don’t make infants grow; they gestate them. They might influence, support, encourage, sometimes thwart (for good or ill), but the infant keeps on growing.

This is what I find so magnificent about the children I work with: despite the most appalling early experiences, they still keep growing! The desire to take the concept of mothering and theorise it as our m/other tongue is an attempt to draw upon the most facilitative aspects of mothering: to intentionally apply these principles within the interdependent space between carer and cared for.

To do that, we have to not force the pace. We might be able to facilitate the pace. We can’t dictate the outcome. We might be able to facilitate some aspects of outcome more than others. To do that we have to work with the material that is natural to the place we are, the relationship that we are in.

Mmm, I think I have heard this before. Isn’t this unconditional positive regard, congruence, and empathy (Rogers, 1957)?

What struck me last month was that a focus on innovation or change can often distract from the cost implications — particularly the loss of power/place in the hierarchy/status — that come with actually living out the theory we already have. In such situations, innovation becomes a way to avoid putting into practice what we know can make the world a better place now. Instead, it shifts our focus to imagining it could be better in the future if only we found ‘the’ answer to ‘have it all’ at no cost to self.

We don’t need to innovate; we simply need to put into action what we already know. What we need is to gently and compassionately explore what is standing in the way of us doing that.

One of the things that may hinder us is the need to choose to use our power in service of others, to relinquish status as defined by the manstream, and to focus on the repetitive, often messy tasks of maintenance. These tasks are largely unacknowledged and unappreciated until they are not done. The low-status tasks inherent in mothering are a significant aspect of creating equality through listening to the voice of the less powerful.

Operationalising our m/other tongue, through the process of Theraplay, then becomes a powerful challenge for us to live in a position of promoting social justice. I called it sacred in the title of this section. This idea came from a quiet Christmas Eve communion service, where I was privileged to watch our two female priests and was moved by the rightness of the ritual being performed by women on the eve of the labour of a woman who had gestated an ontological and epistemic game-changer for our world (if only the world could hear and make concrete such a message of love).

While I may process the aspects of tacit knowledge that Polanyi calls ‘ineffable’ through Christian spirituality, I strongly believe any spiritual practice that is grounded in the ineffable will be saying the same thing — again, feel free to debate.

But it is hard, this facilitating maintenance of our m/other tongue, made harder when the labour of caring is not being seen. Sacred care seems to be at the opposite end of the spectrum from capitalism or the neoliberalism prevalent in our current white, global North cultures. Using our power in the service of the less powerful other, to facilitate their path to fulfilment in the world is, I believe, sacred care.

Conclusions

It is time to stop writing for this month. I look back and think I haven’t argued through points thoroughly. There is so much more thinking I want to do on the craft of maintenance. I don’t know if the notion of sacred maintenance or sacred care stands up. I remind myself that this is a place of gestation, the start of a project that in my ethical application I said would take five years. I remind myself that I am not writing for the manstream. I am writing for me, to help myself understand what I do in the hope it will help you too. It will take the time it takes, but I hope sharing the process is illuminating in itself. I am choosing to share this as a punctuation point in the process, not a fully formed end — just a snapshot of where things are at.

Having a laugh: no manual, just a m/other-us-all

One of the things you asked me to hold in mind in my data generation project was where humour fitted in our m/other tongue. I found this difficult as the pathway to illuminating and operationalising our m/other tongue requires me to face a lot of personal resistances and pains. However, I am finding that in subverting language I do find some fun!

So here is the start of our handbook of operationalisation of our m/other tongue.

Building a m/other-us-all to operationalise our m/other tongue (not a manual, a man telling you all what to do, but who doesn’t do it himself!)

Our three core principles. We commit to:

Not knowing/letting go

Dependence/interdependence

Faithfulness

(Peacock, 2023)

We do this by daily asking ourselves the following questions (to be added to each month as I subvert a desire by the manstream to go by the manual).

Who do I want to care for today? (see The world is not a nice place. Can m/other tongue help things to change?)

What care-full maintenance do I wish to attend to today in celebration, joyfulness, and admiration of that maintenance action and the relationships it might facilitate? (i.e. not focusing on searching for the answer to make things better)

Always my end place is to say to you: It is like this for me. Is it like that for you too?

Research update

What I’ve done this month

See above!

What I want to do

Start a glossary. I am aware there are some terms that are emerging that have specific meanings as I try to transfer the ‘more than I can say’ experience into words. I feel like I want to be consistent in my use of terms like manstream and Theraplayer. A glossary should help us all keep track of what they mean without me having to refer you back to previous posts.

What you can do to be part of this research

Tell me what words you think should be in a glossary!

Let me know if you’ve come across people who seem to be saying the same thing as me — think how powerful our joint information super-encountering exploits could be and how we can create a deep web of understanding from multiple theoretical perspectives.

Challenge me where my ideas need more working through.

Be part of the conversation through the comments, by talking to colleagues, by referencing these posts in your writing (remember to challenge the manstream view of what is ‘good quality’ literature by saying it is an explicit choice on my part to circumvent published and peer-reviewed literatures to make space for new ways of writing and thinking about knowing. But do critique whether you think what I write is good quality!).

Bibliography

Harvie, J. (2013). Fair play: Art, performance and neoliberalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Leavy, P. (2013). Fiction as research practice: Short stories, novellas, and novels. Left Coast.

Lorde, A. (2018). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=8D57C658-66D4-401C-891E-9BC385F65341.

Moustakas, C. E. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage.

Ottinger, G. (2023). Responsible epistemic innovation: How combatting epistemic injustice advances responsible innovation (and vice versa). Journal of Responsible Innovation, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2022.2054306.

Papadopoulos, D., Puig de la Bellacasa, M., & Tacchetti, M. (Eds.). (2024). Ecological reparation: Repair, remediation and resurgence in social and environmental conflict. Bristol University Press.

Peacock, F. (2023). What did I do? I don’t know. Generating fiction to examine the tacit maternal knowing I bring to my Theraplay® practice with children who are experiencing relational and developmental trauma. (Doctoral thesis) [Doctor of Education, University of Cambridge]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.80181.

Polanyi, M. (1973). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Polanyi, M., & Sen, A. (2009). The tacit dimension. University of Chicago Press.

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357.

Sela-Smith, S. (2002). Heuristic research: A review and critique of Moustakas’s method. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 42(3), 53–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167802423004.